Even Modest Densification Could Yield Millions of New Homes

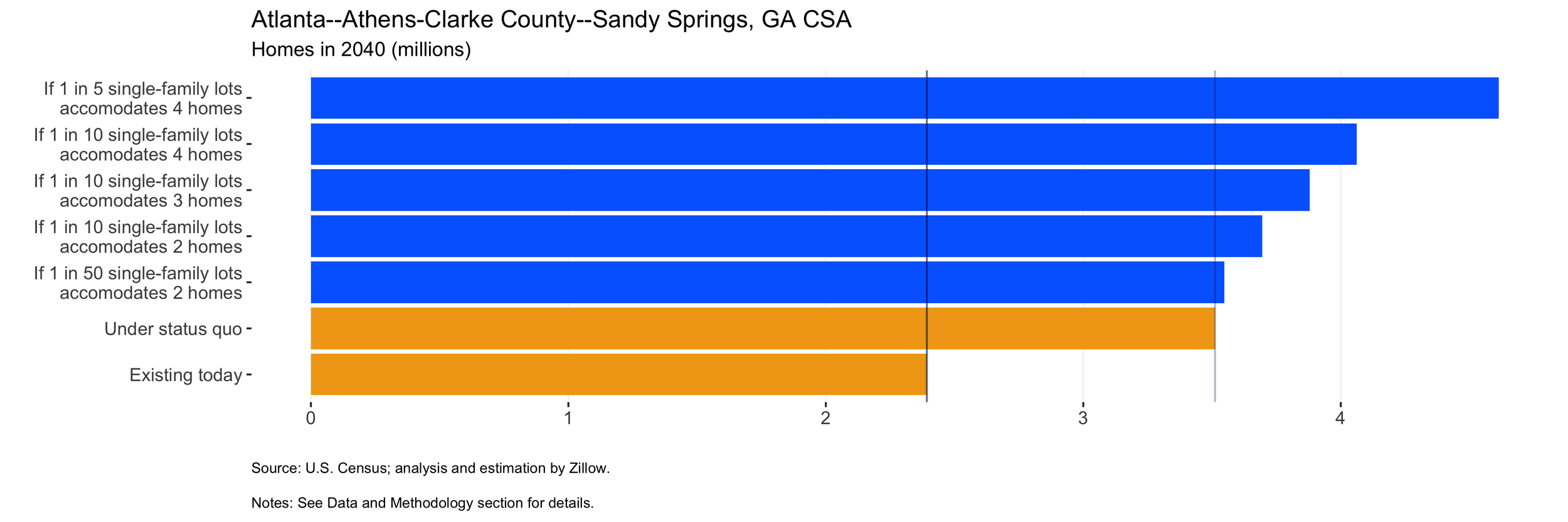

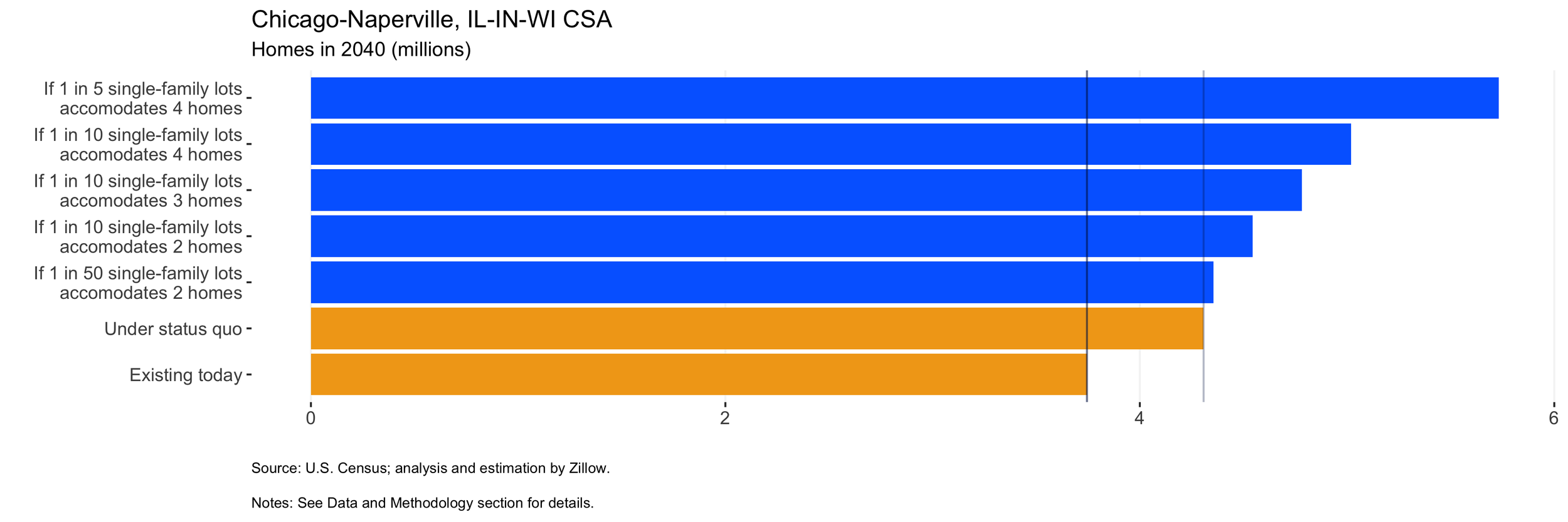

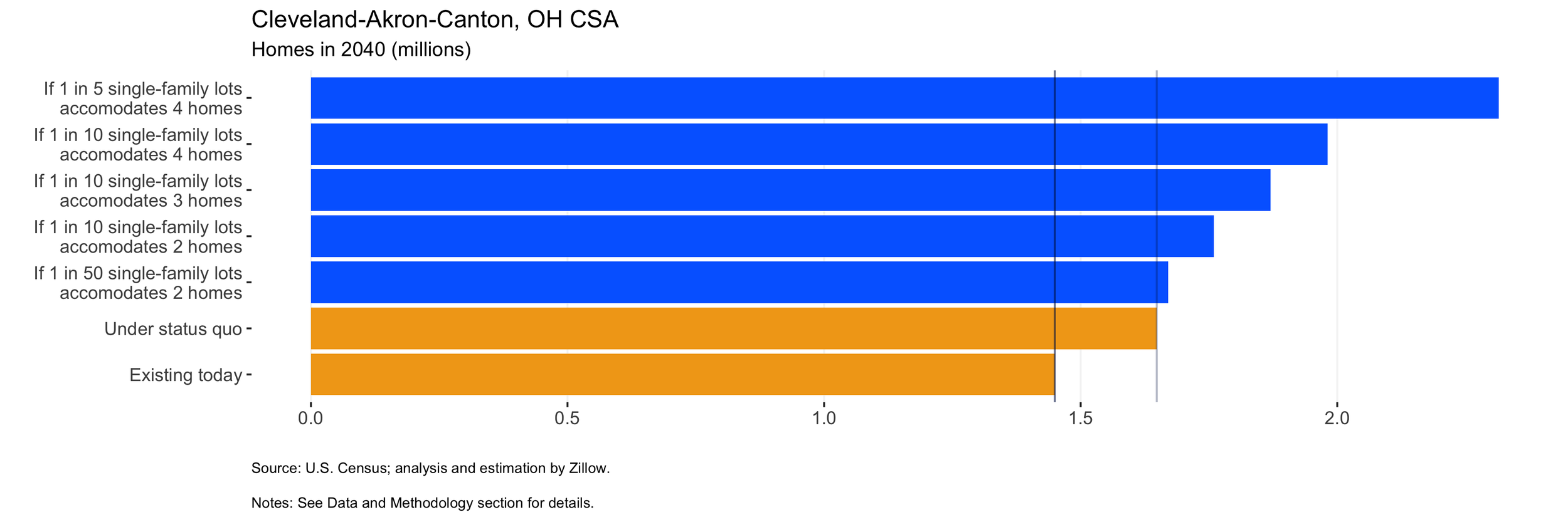

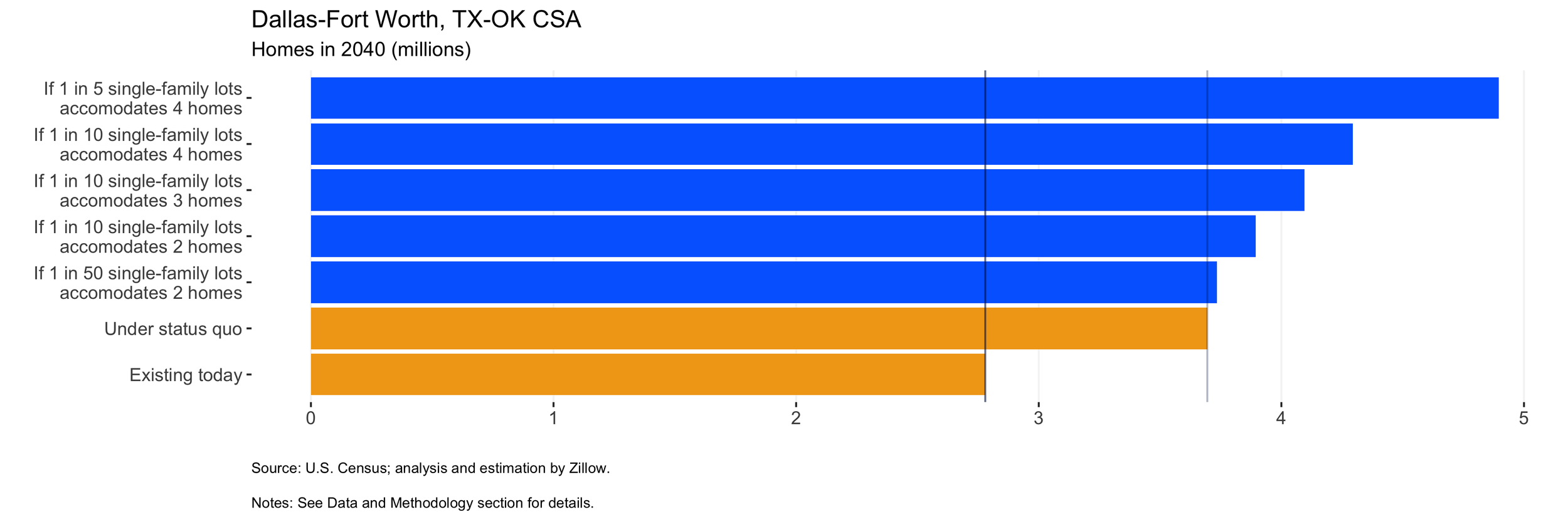

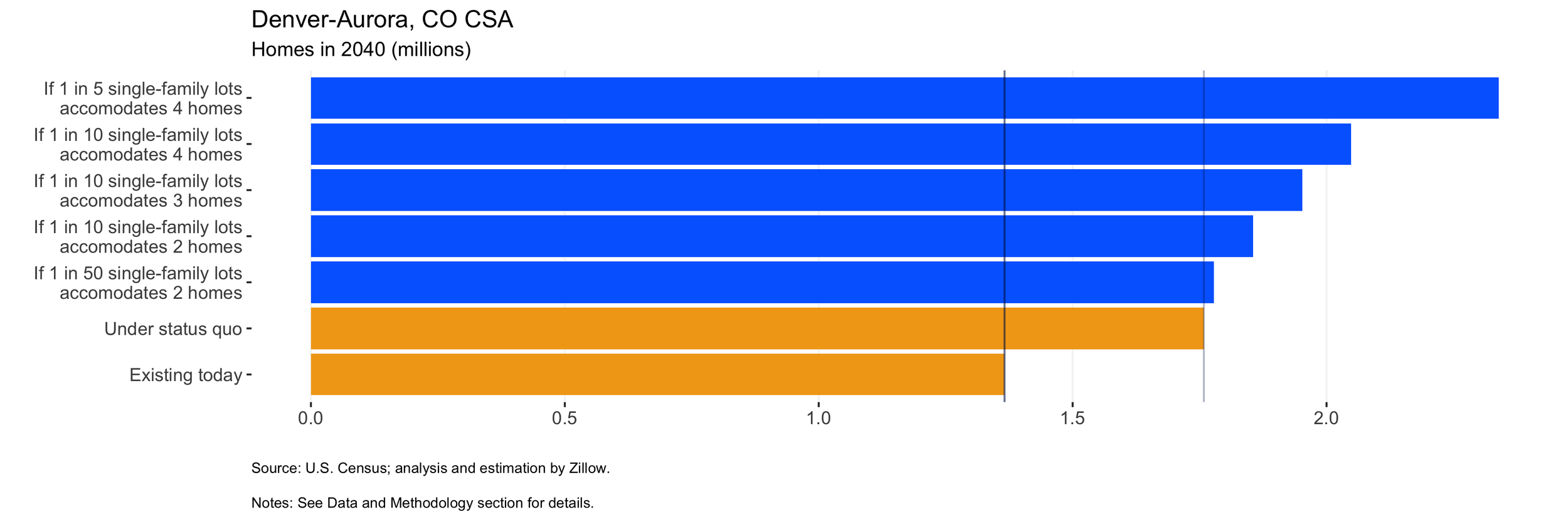

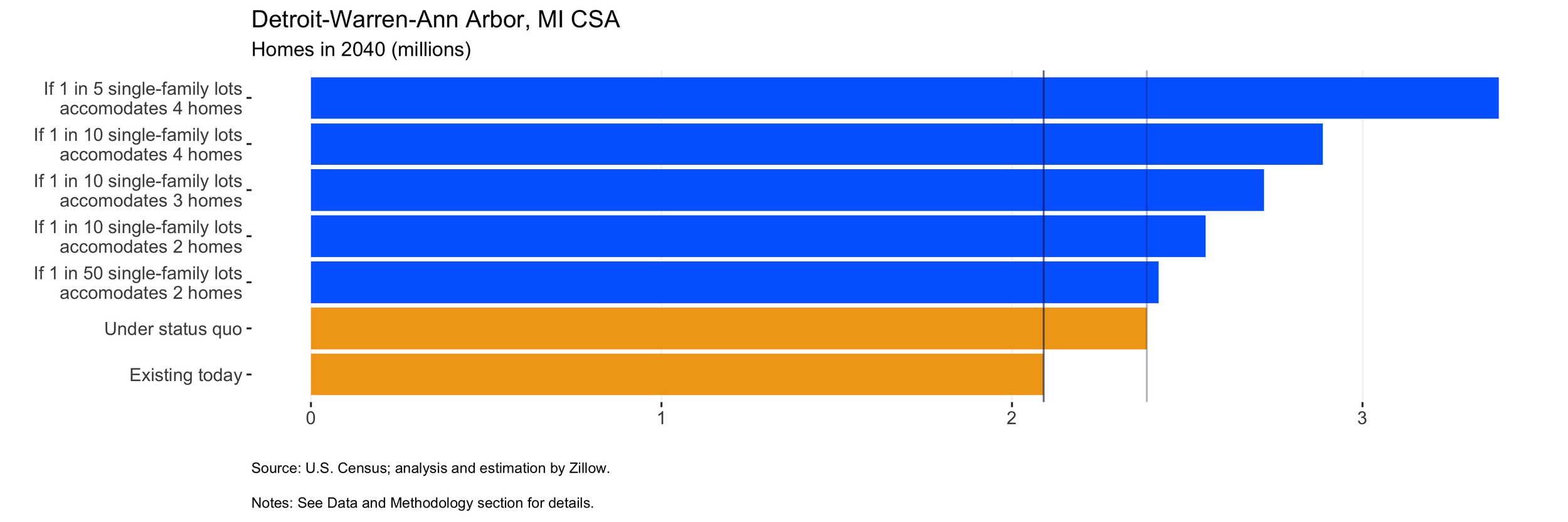

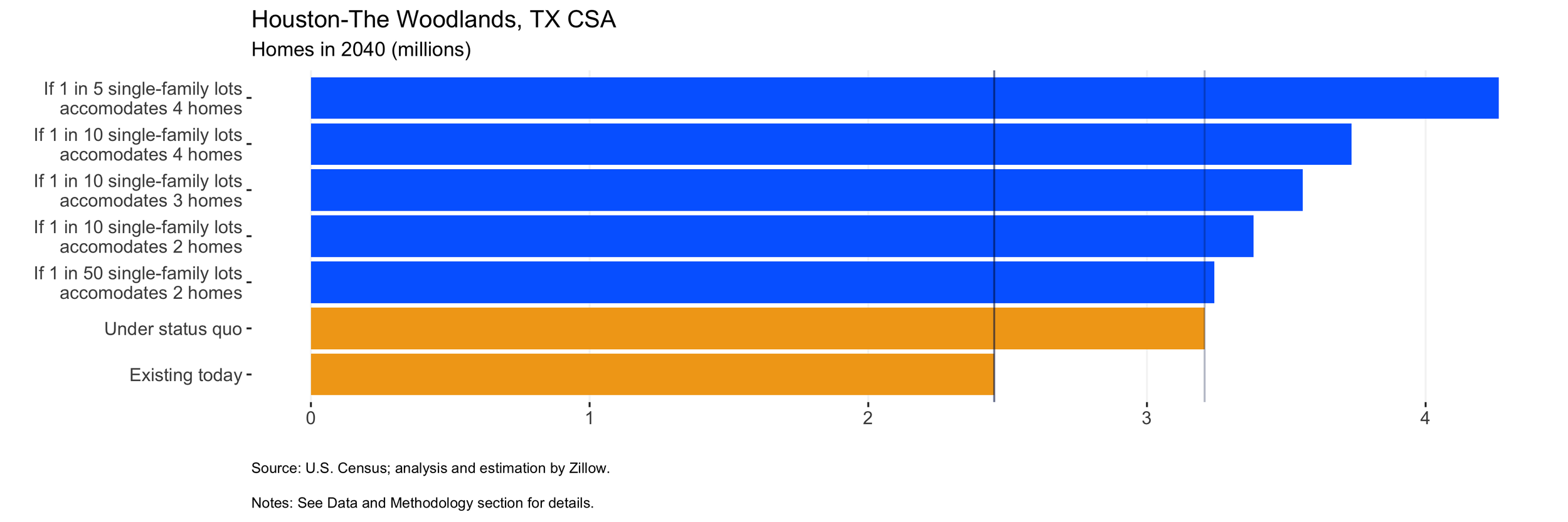

Across 17 metro areas analyzed, allowing 10% of single-family lots to house two units instead of one could yield almost 3.3 million additional housing units to the existing housing stock. That’s on top of the roughly 10 million already expected to be built through 2040 under status quo assumptions.

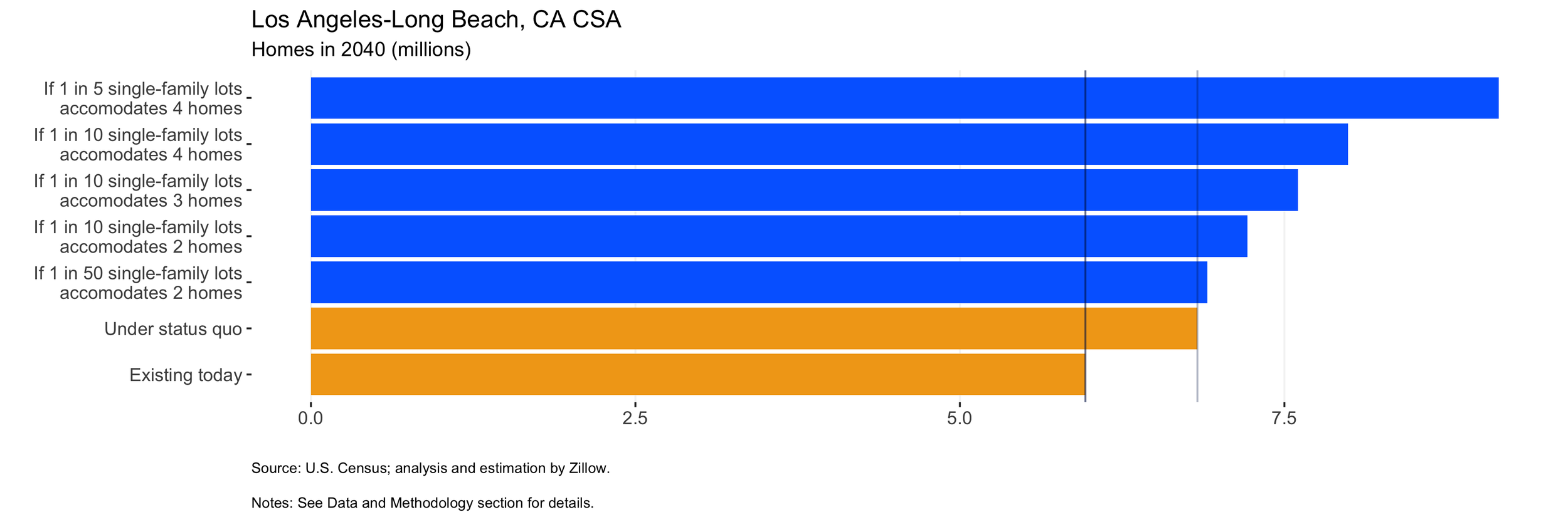

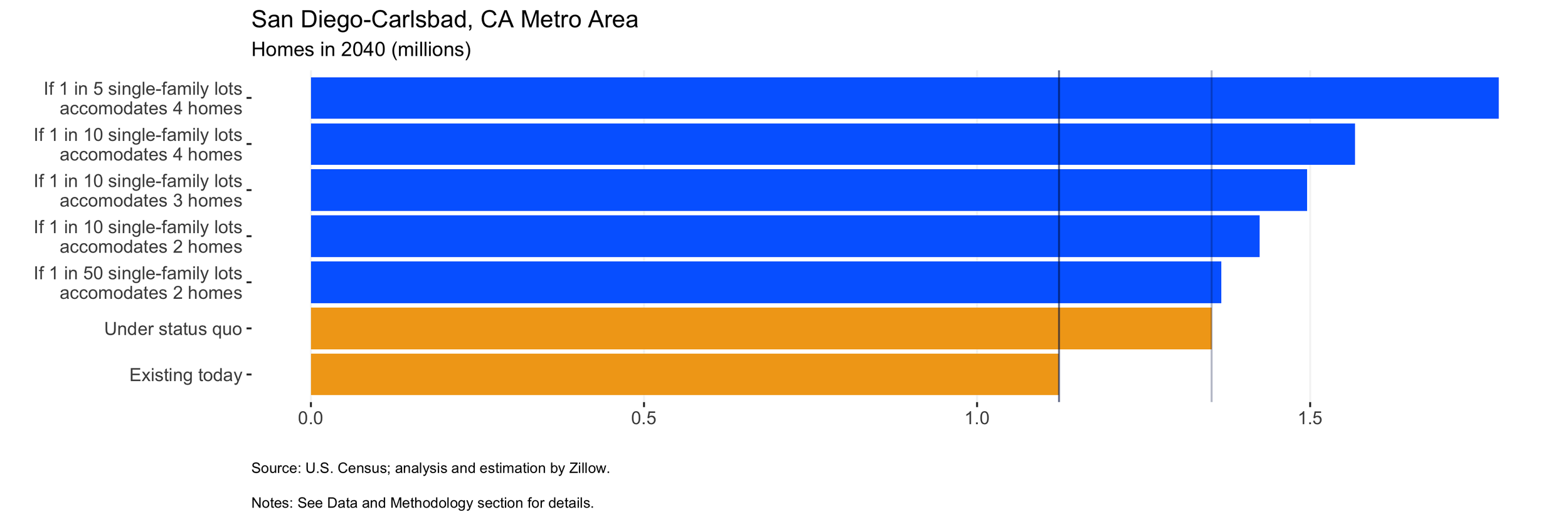

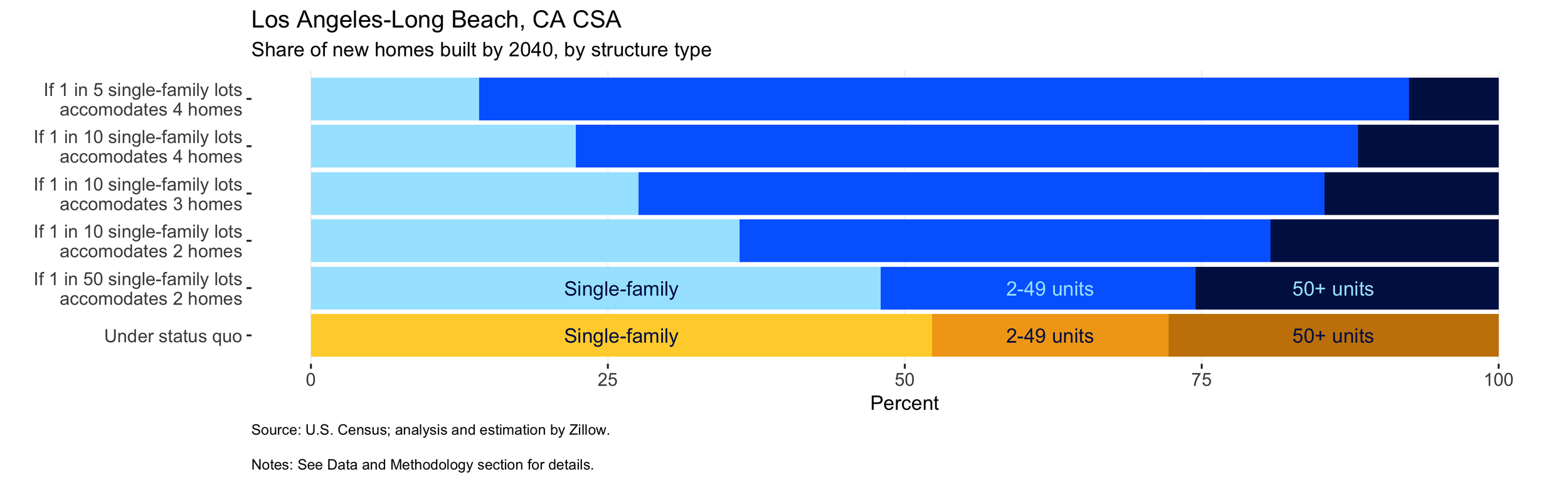

In the L.A. region, if 1 in 5 single-family lots were re-zoned to hold two homes, the local housing stock could be boosted by 775,000 homes. Allowing four homes instead of two on those same 20% of single-family lots could yield a housing stock increase of more than 2.3 million homes, or a 53.4% boost over the current stock when combined with homes already expected to be built.

Under a number of scenarios, the extent of new housing provided by modest densification could exceed what is likely needed to meaningfully slow housing price growth over the long term relative to the unsustainably rapid pace of recent decades, even in the most expensive coastal metros.

Editor’s Note: The expensive coastal cities’ current housing affordability crisis has been decades in the making, the result of slowing metropolitan growth in the face of sustained housing demand. This piece explores how much new housing could be added in a handful of large markets if current density restrictions in single-family zoned areas were relaxed. For a deeper dive into the historic building trends that have contributed to this crunch we encourage you to read our research here.

Allowing for even modest amounts of new density in the nation’s overwhelmingly single-family dominant locales could lead to millions of new housing units nationwide, according to a Zillow analysis, helping alleviate a housing affordability crisis that has been decades in the making.

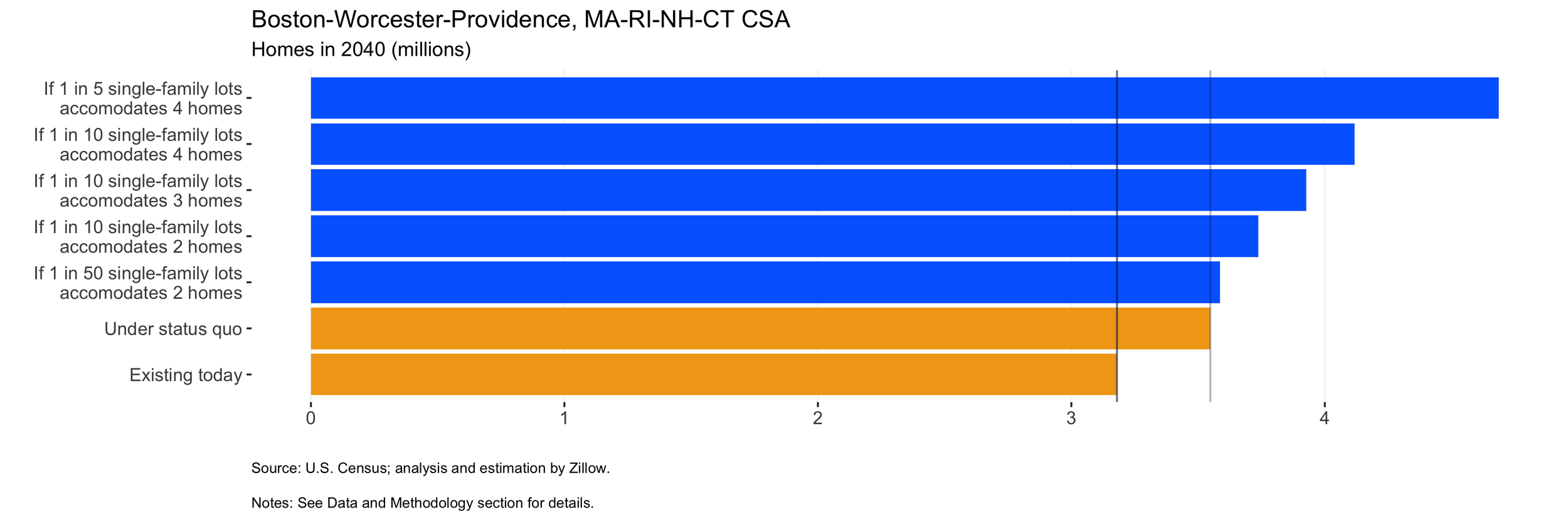

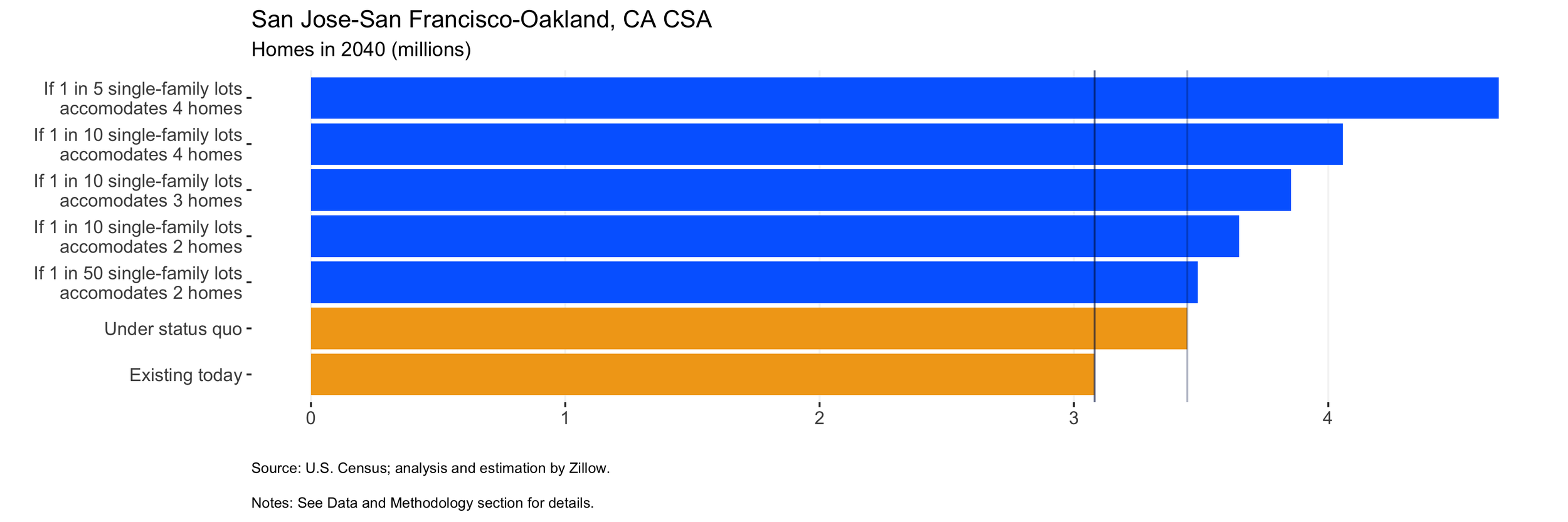

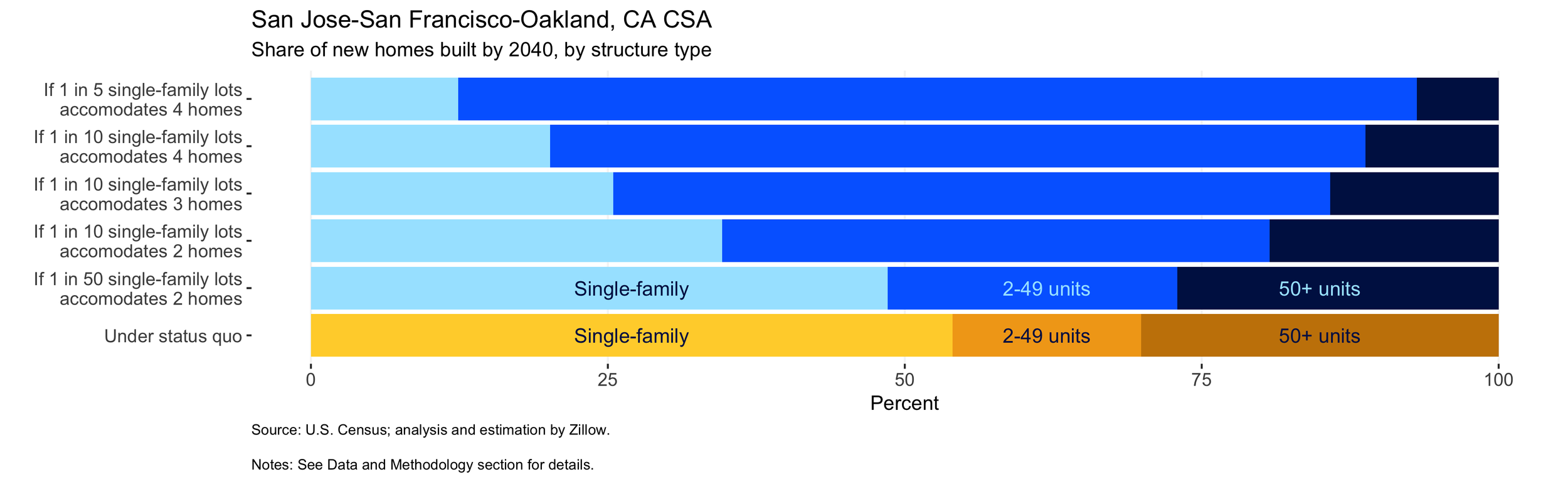

If the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, continues to add housing largely as it has over the past two decades – in single-family homes on the periphery and in distinct clusters of large multifamily buildings – it could grow its housing stock by an estimated 11.8 percent over the next two decades. But if just 1 in 10 lots currently home to a single-family residence were redeveloped or otherwise allowed to accommodate two homes, the area’s housing stock could grow by 18.4 percent over the same period – or more than 200,000 homes beyond the status quo.

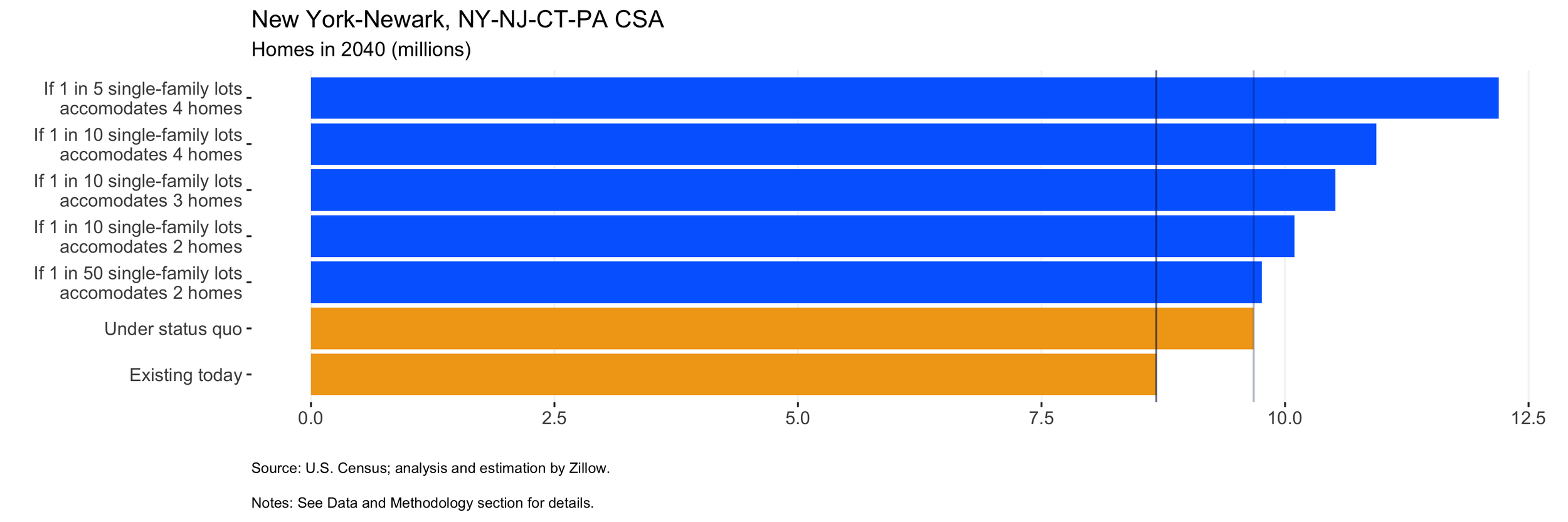

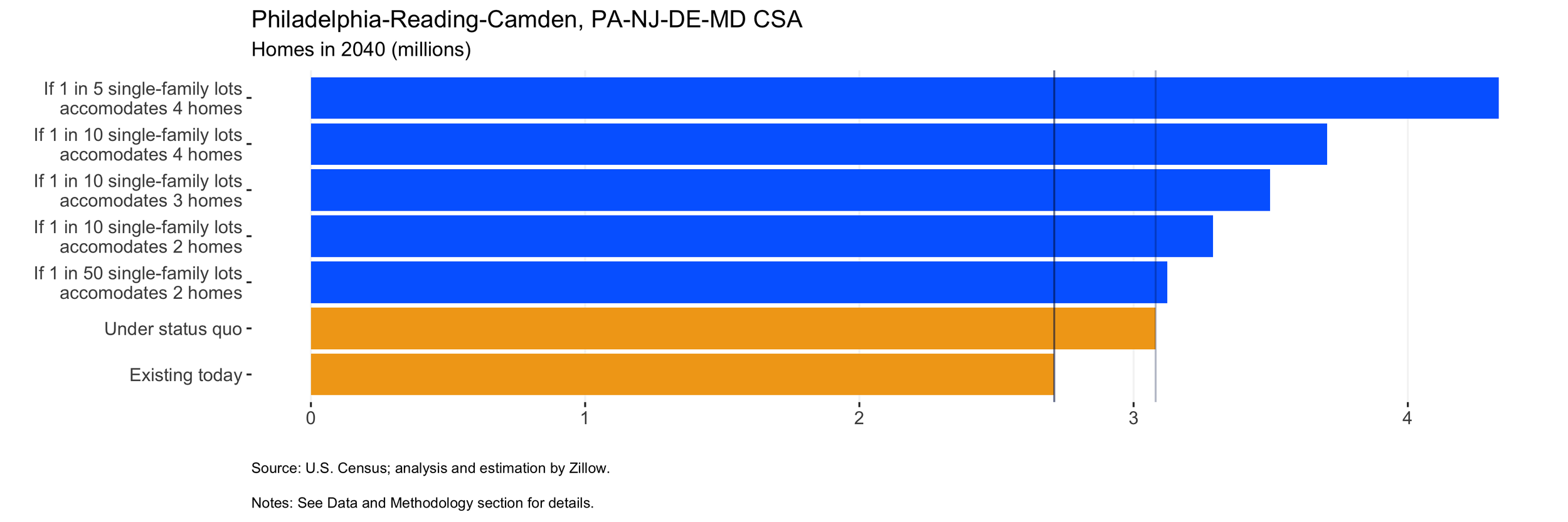

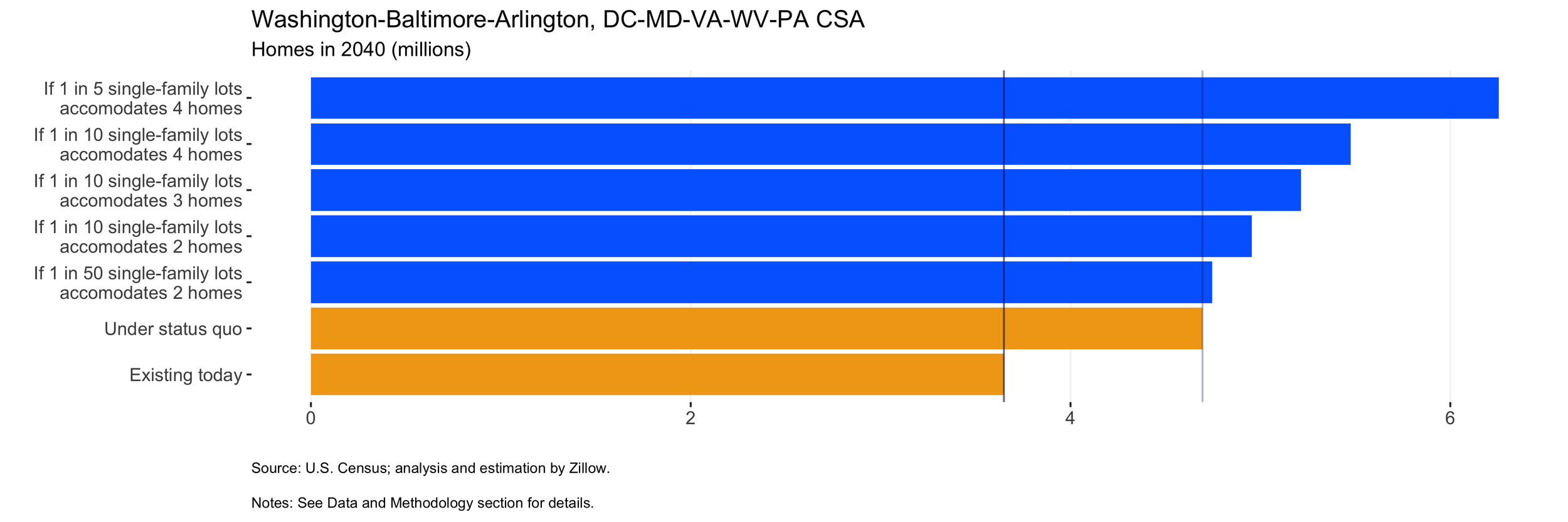

Over the next two decades, building at the status quo is expected to yield a total of roughly 10 million new homes across the 17 large metros analyzed nationwide, a more than 20% boost over the almost 50 million homes these markets currently collectively contain. Allowing for two units on just 10% of single-family lots would add another approximately 3.3 million homes on top of that 10 million, a boost of almost 27% over current levels.

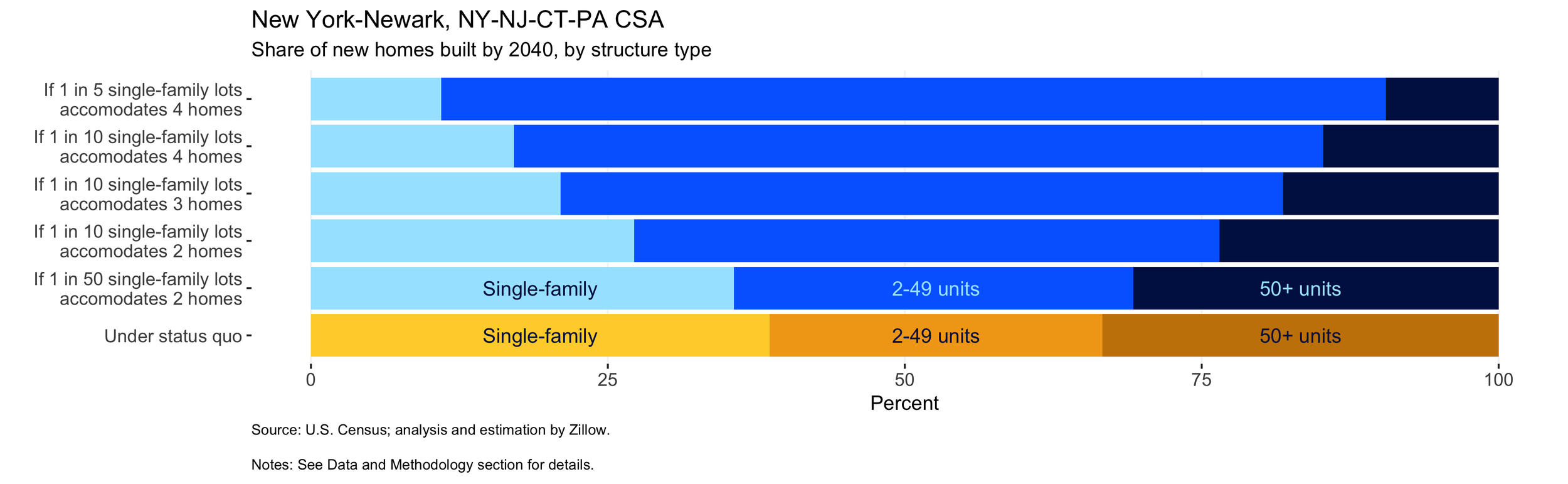

As the outward expansion of America’s expensive coastal cities has slowed in recent decades in the face of natural barriers and environmental concerns, most new housing development has been confined to islands of density – often near transit or in formerly non-residential areas – in an otherwise stagnant sea of no-growth. Looking inward at already-developed single-family tracts and allowing for two, three or even four homes where just one stands today could reignite housing development without contributing to sprawl.

This analysis quantifies the large potential benefits to housing supply that could be gained by making even small changes to the existing single-family housing stock. Zillow estimates that the Los Angeles region could theoretically expect to add a little more than 863,000 housing units over the next two decades if building trends continue as they are – about a 14.5% increase. Allowing for 1 in 10 single-family lots to accommodate two homes could add another 386,805 homes on top of that – combined, an almost 21% increase over the current housing stock.

Squaring the Circle

Single-family neighborhoods account for the lion’s share of land in metropolitan America, and over the years have generally become insulated from denser redevelopment by a thickening tangle of regulations, reflecting entrenched local interests that benefit from keeping a neighborhood as it is. And a shortage of new housing development coupled with sustained demand for it, especially in the nation’s pricey, coastal cities, has contributed mightily to an affordability squeeze.

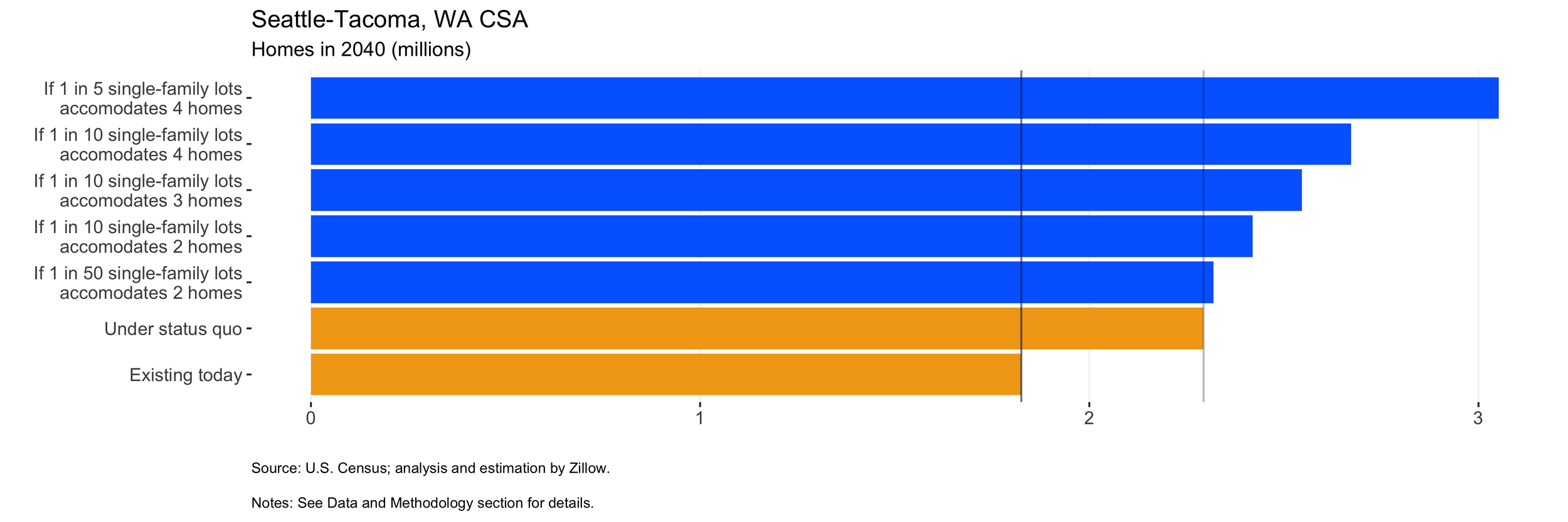

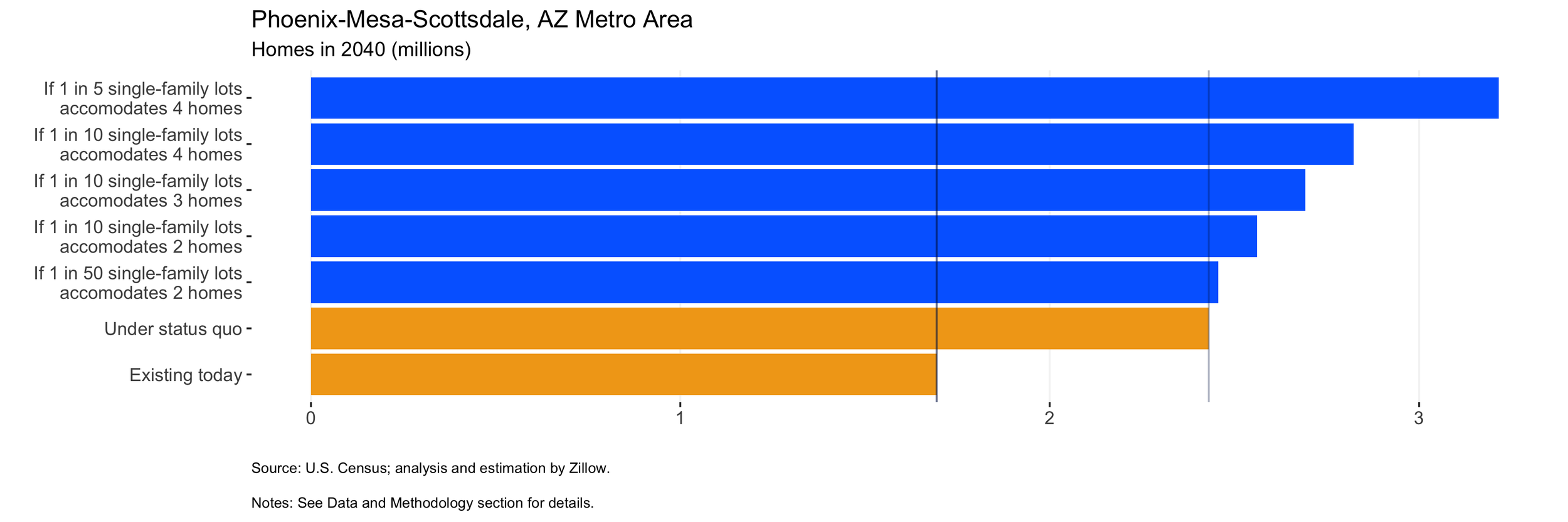

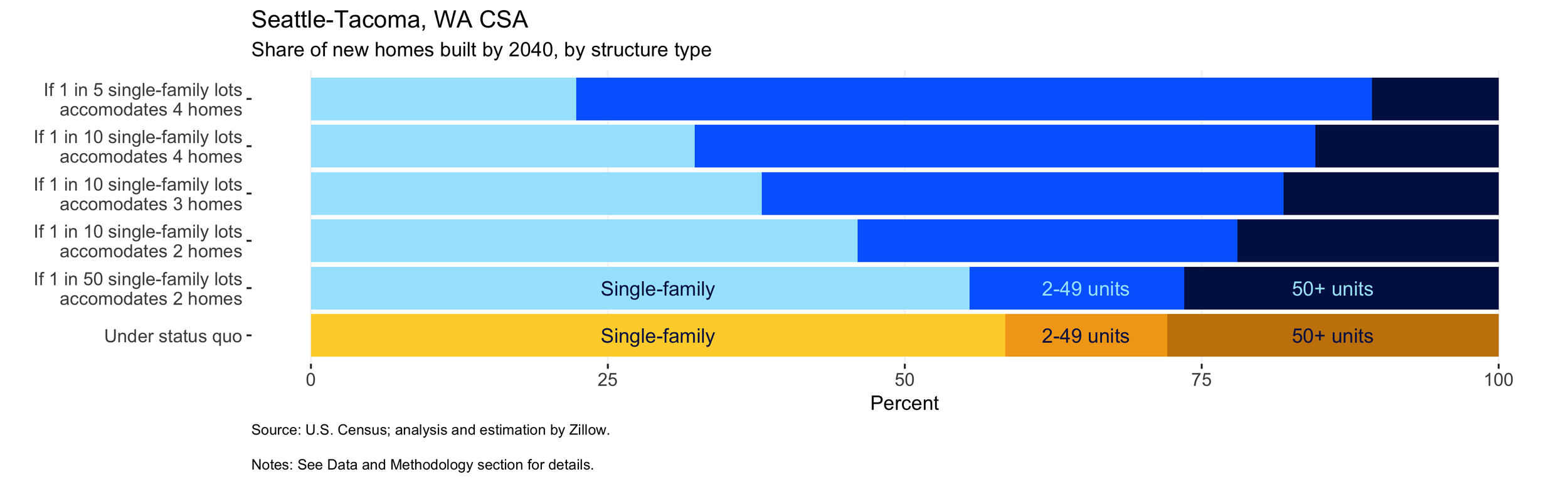

This is easy to see in a handful of rapidly appreciating West Coast markets where it has proven more difficult to build significant new housing supply in recent decades. Over the past 20 years,[1] the median home value in the Los Angeles metro area has risen 102.9% in real terms; 91.8% in the San Francisco metro; and 64.6% in the Seattle area. In contrast, metros in the South where it has historically been much easier to build new homes, especially on the periphery, experienced great population growth but relatively little housing price appreciation. Examples include Houston (10.4%) and Atlanta (11.2%).

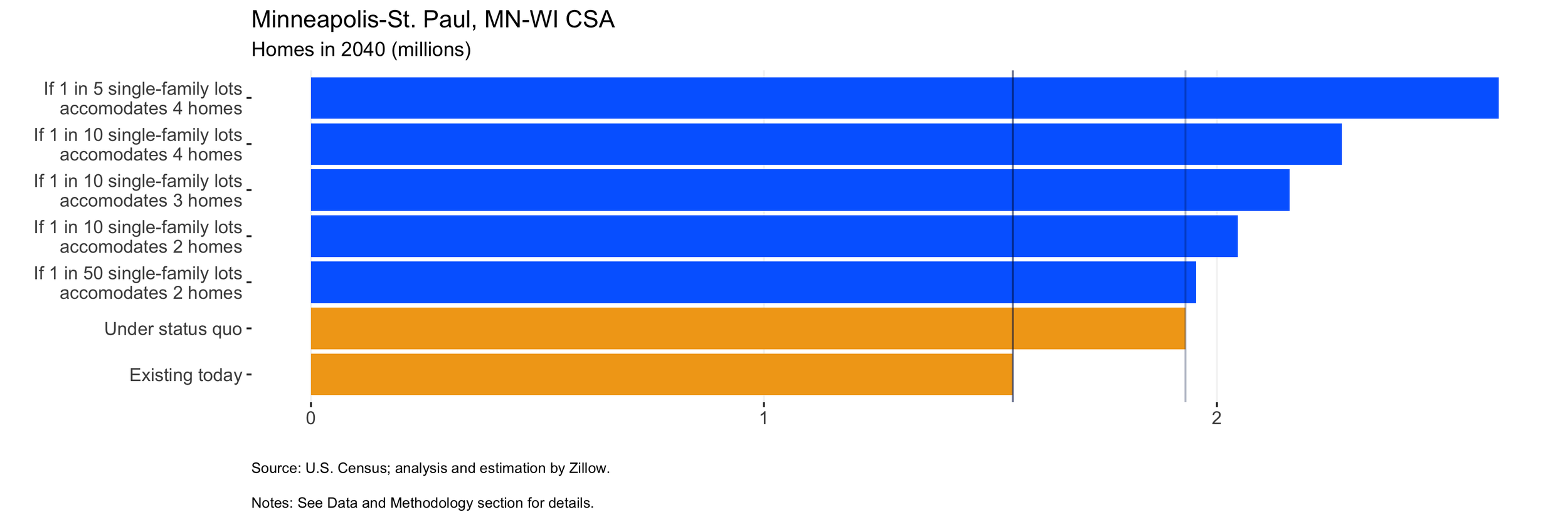

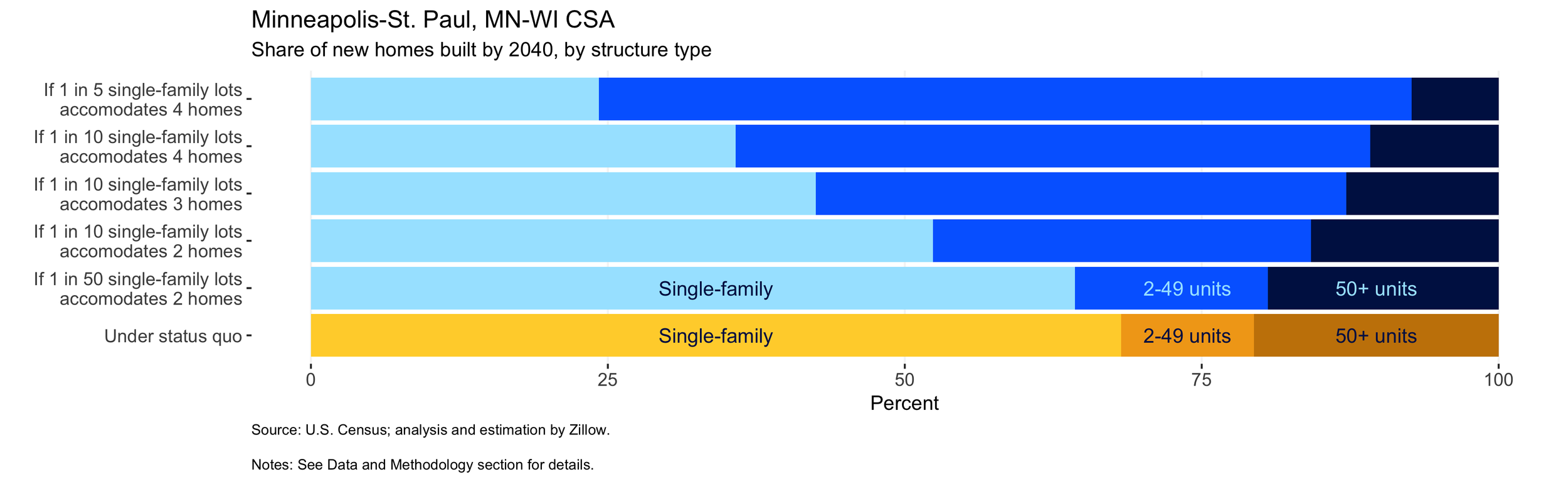

There are fears that intense densification may risk turning leafy neighborhoods into an urban concrete jungle, leaving many searching for a way to square the need for more housing with the desire to avoid altering the physical nature of entire swathes of the nation’s urban and suburban fabric. But in practice, allowing just 1 in 10 single-family homes in a given neighborhood to host a livable in-law suite above the garage or a bachelor apartment in the basement isn’t likely to drastically alter an existing streetscape. However, it could still contribute meaningfully to new housing supply as metros grow increasingly unaffordable. And as this thinking has evolved, re-zoning the nation’s archetypical single-family neighborhoods to allow for modestly denser housing development has gone from unthinkable to reality in a handful of places, notably Minneapolis and Oregon.

Redeveloping more single-family lots and/or allowing them to host a triplex/quadplex or a row of four townhomes may result in more noticeable change than allowing for just two homes, but it’s difficult to ignore how much the numbers differ under these scenarios. In the L.A. region, if twice as many single-family lots – 20% instead of 10% – were re-zoned to hold two homes, the housing stock could be boosted by almost 775,000 homes. Combined with the 863,000 homes expected to be built under the status quo, this represents an almost 27.5% increase over the existing stock. Allowing four homes instead of two on those same 20% of L.A. single-family lots could yield a housing stock increase of more than 2.3 million homes, or a 53.4% boost over the current stock when combined with homes already expected to be built.

How much housing could modest densification add?

Click on the chart to move to the next metro area:

The Missing Middle

We can also take this exercise to the extreme and suppose every single-family parcel were to host four homes. In the San Francisco Bay Area, that alone would increase the existing local housing stock – not just the estimate of status quo new construction – by 199 percent. Combined with the estimated status quo addition, it would more than triple the entire housing stock. Assuming that demand for that much housing in the Bay Area exists, it would raise the region’s population from its current 9.67 million residents to just over 30 million (holding the current number of residents per home fixed).

That number may seem outlandishly large, and that’s the point! Such immense housing stock growth makes it likely that the amount of new housing made possible through modest densification would be sufficient to meaningfully slow housing price growth over the long term relative to the unsustainably rapid pace of recent decades. Slower growth would make it easier for low- and moderate-income buyers and renters to afford to move to these currently pricey areas and take advantage of the economic opportunities they provide, and may make it easier for long-time residents to afford to stay.

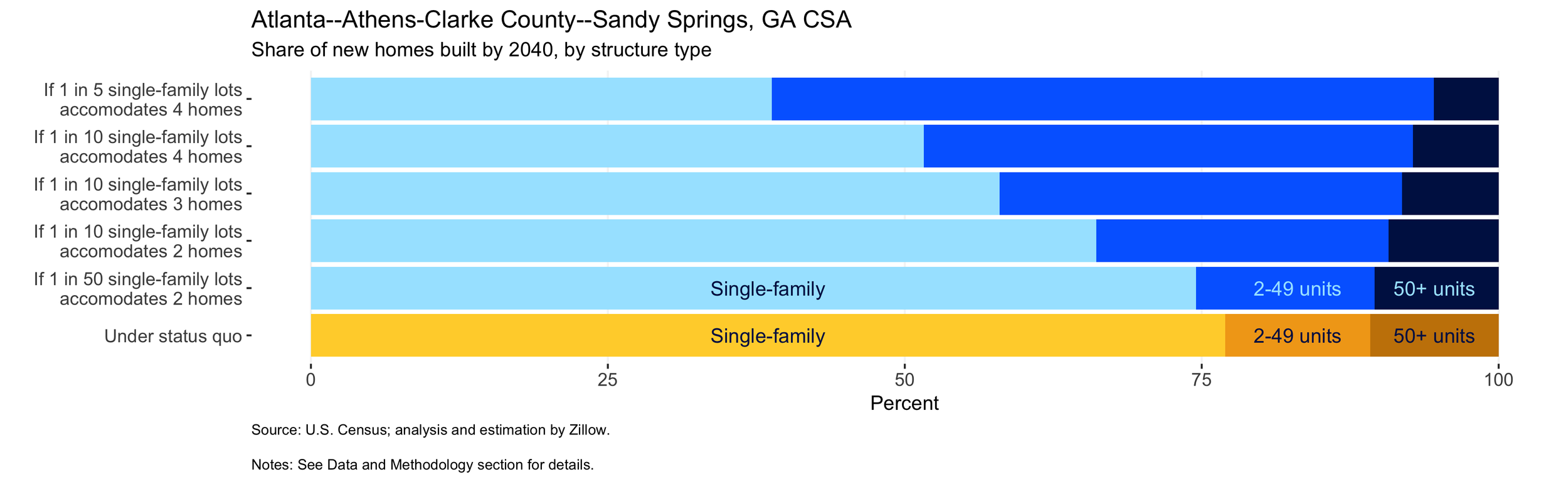

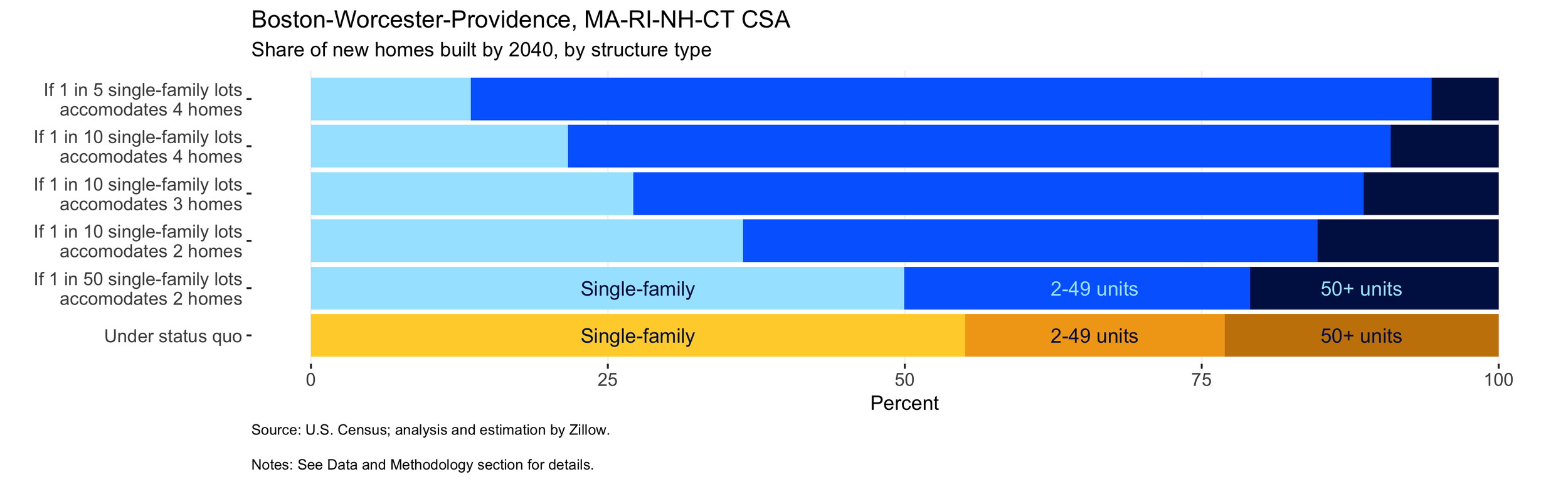

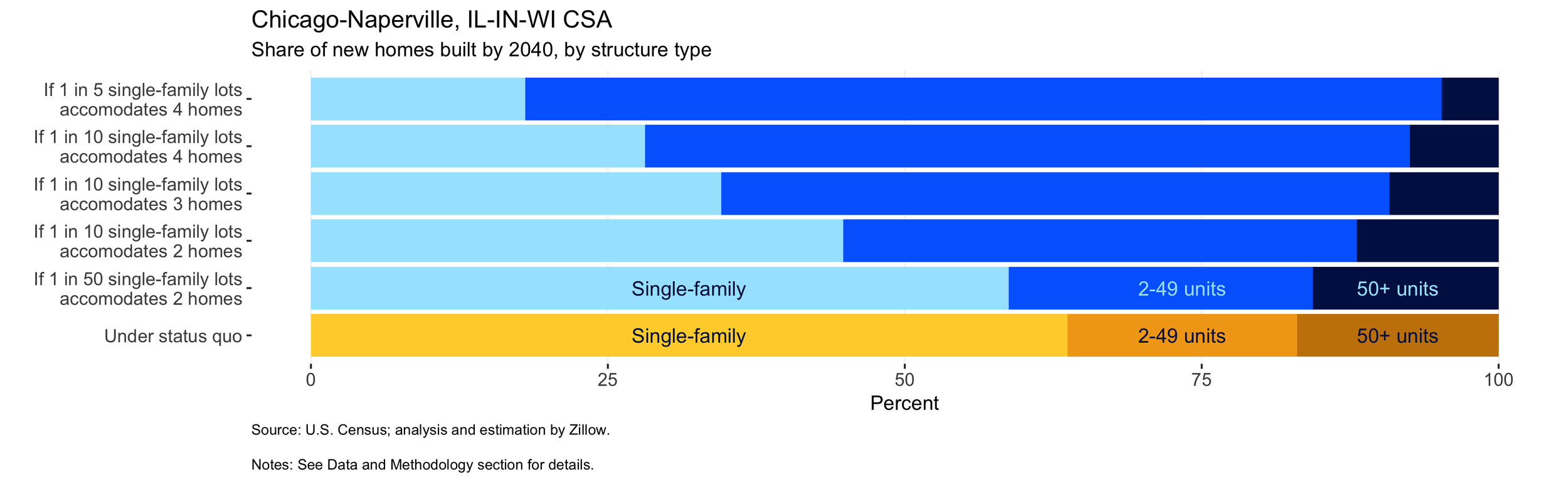

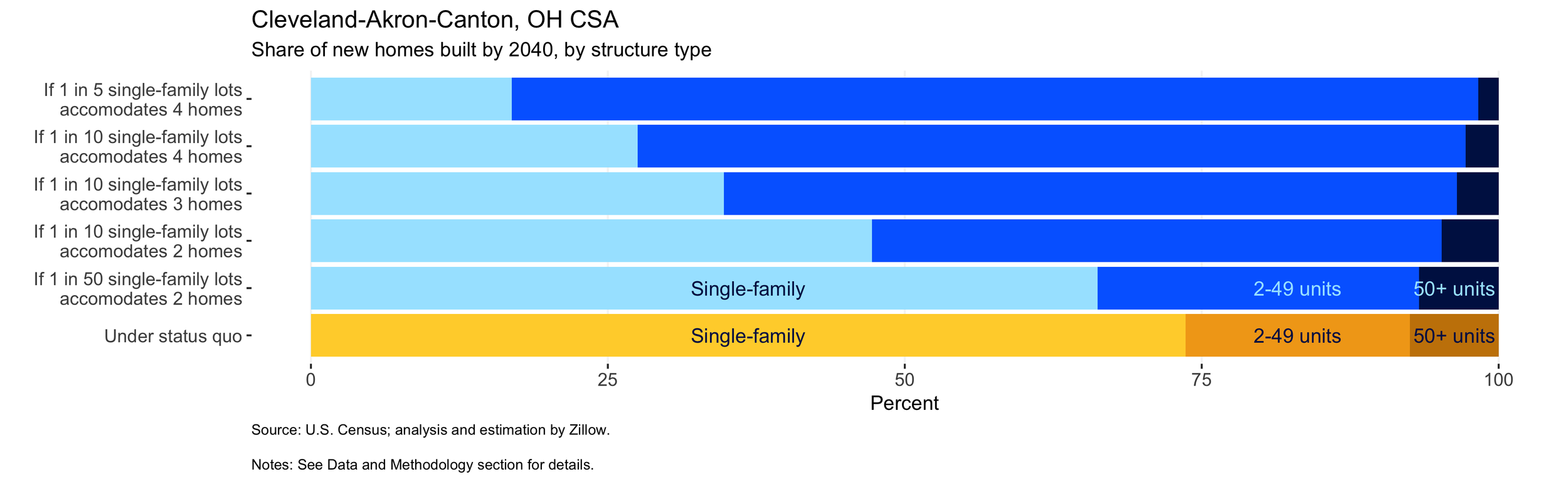

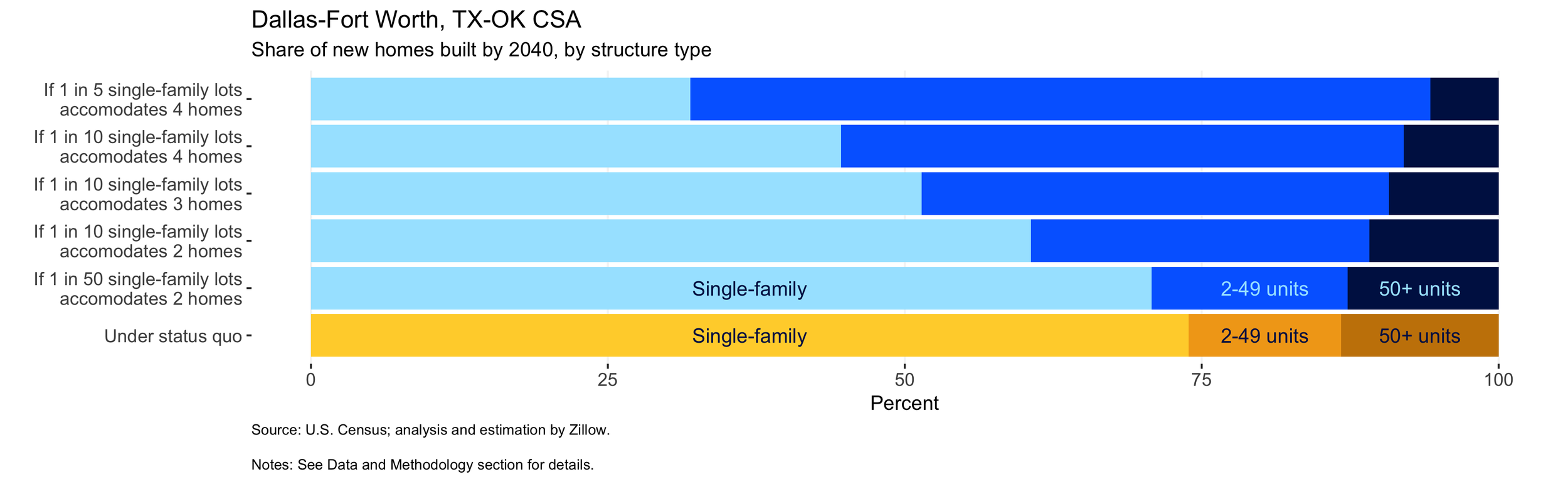

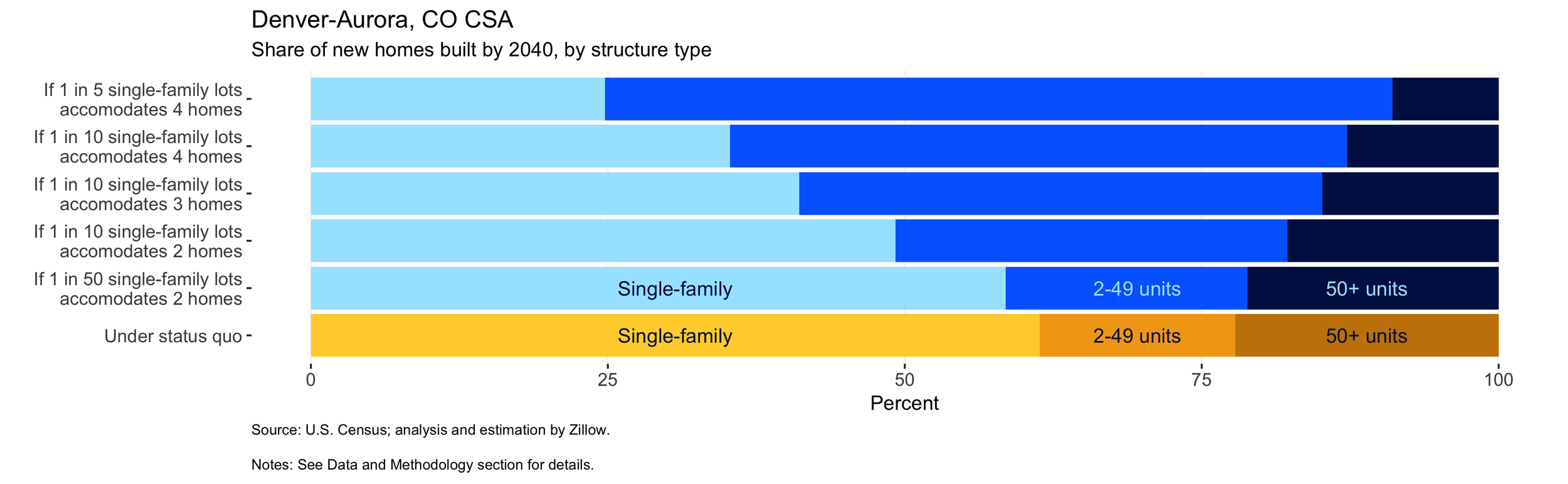

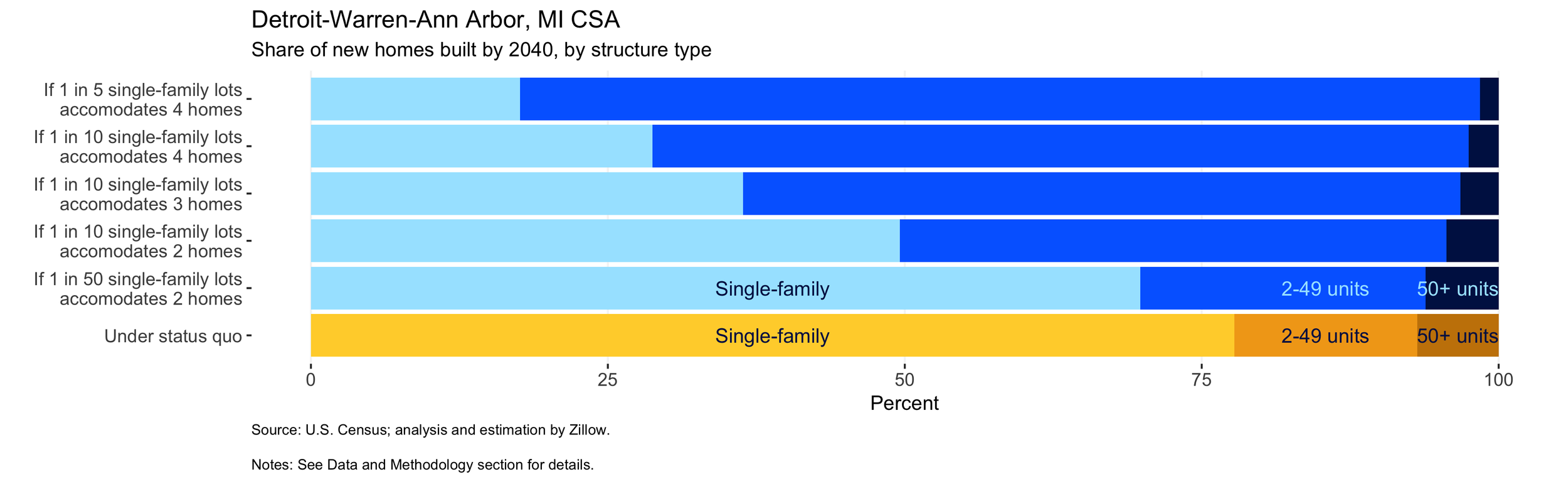

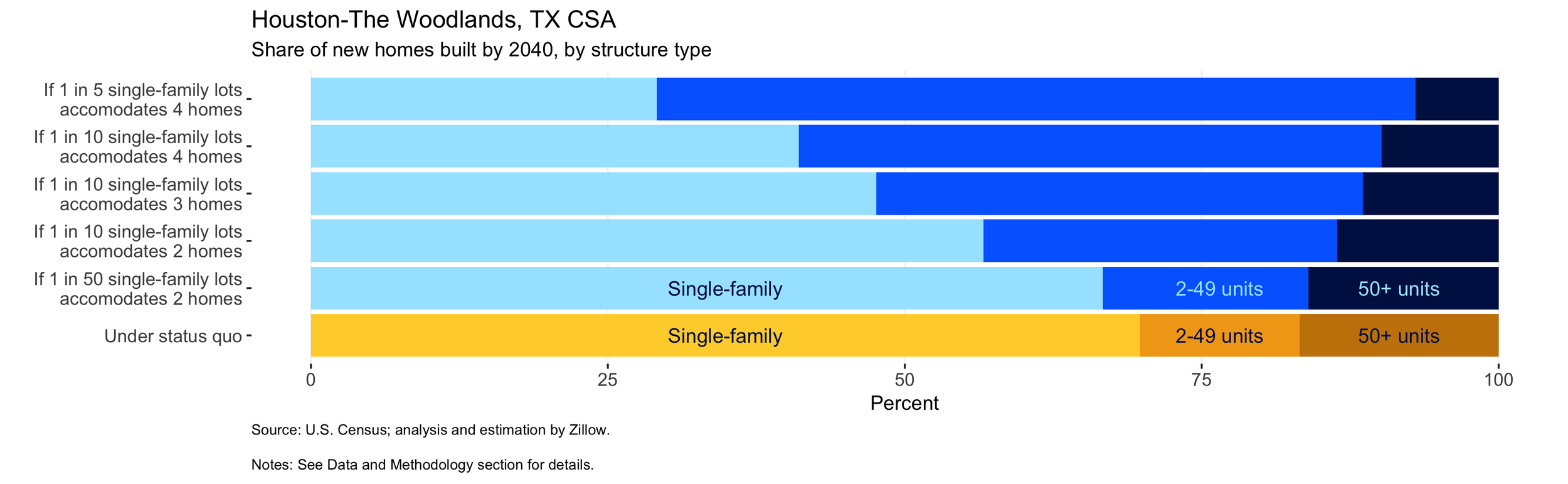

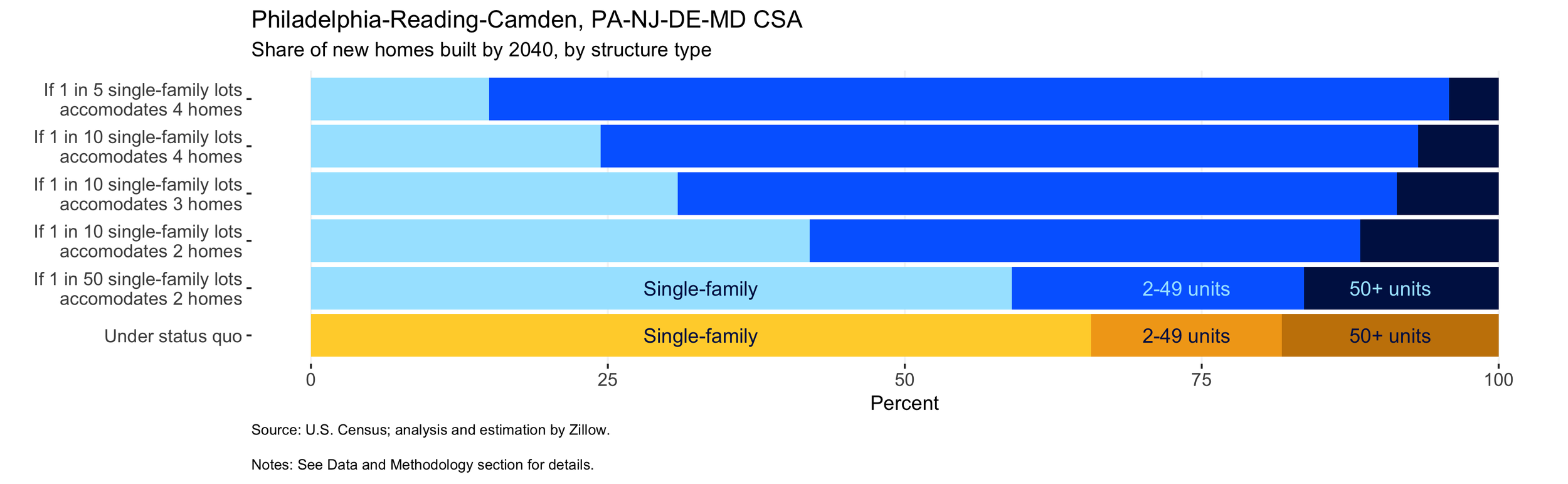

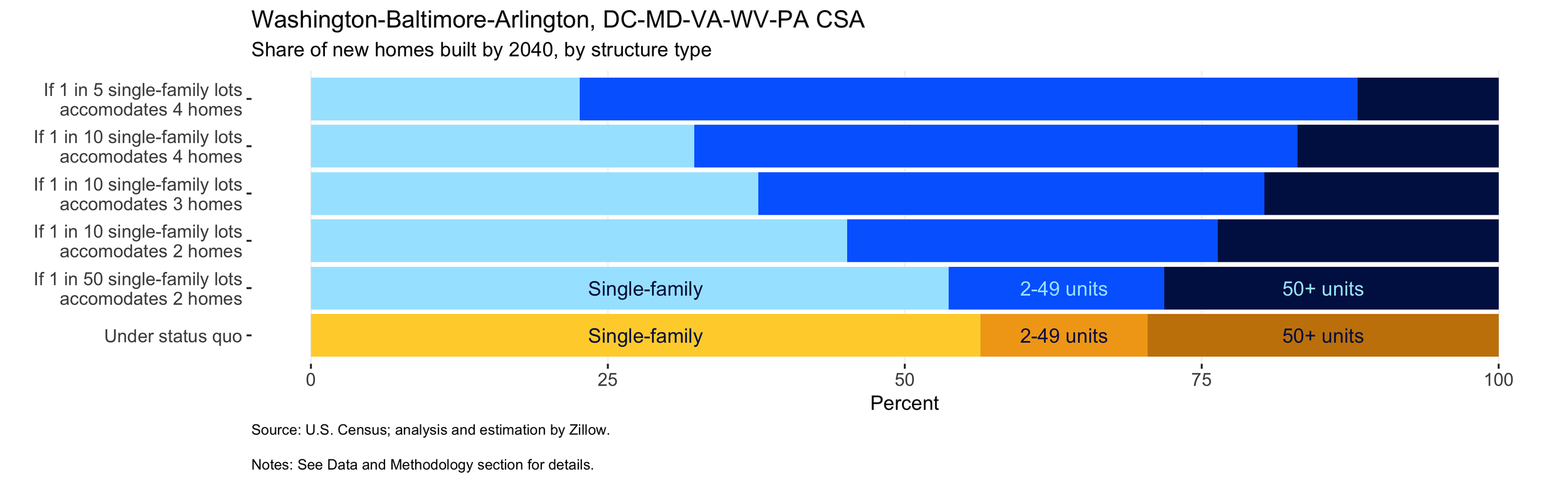

Finally, in addition to simply adding more homes, allowing for some measure of modest densification is also likely to expand the range of home types available to would-be residents. While the status quo is likely to produce mostly single-family homes and units in very large apartment buildings, modest densification would enrich the mix by creating so-called “missing middle” housing in two-to-four-unit buildings. In an environment in which single-family homes are largely out of reach for most, building a variety of housing types that are more affordable seems warranted. If such new housing types also include options that are more spacious and/or bucolic than large apartment buildings, that would broaden consumers’ choices and would be especially likely to benefit young families.

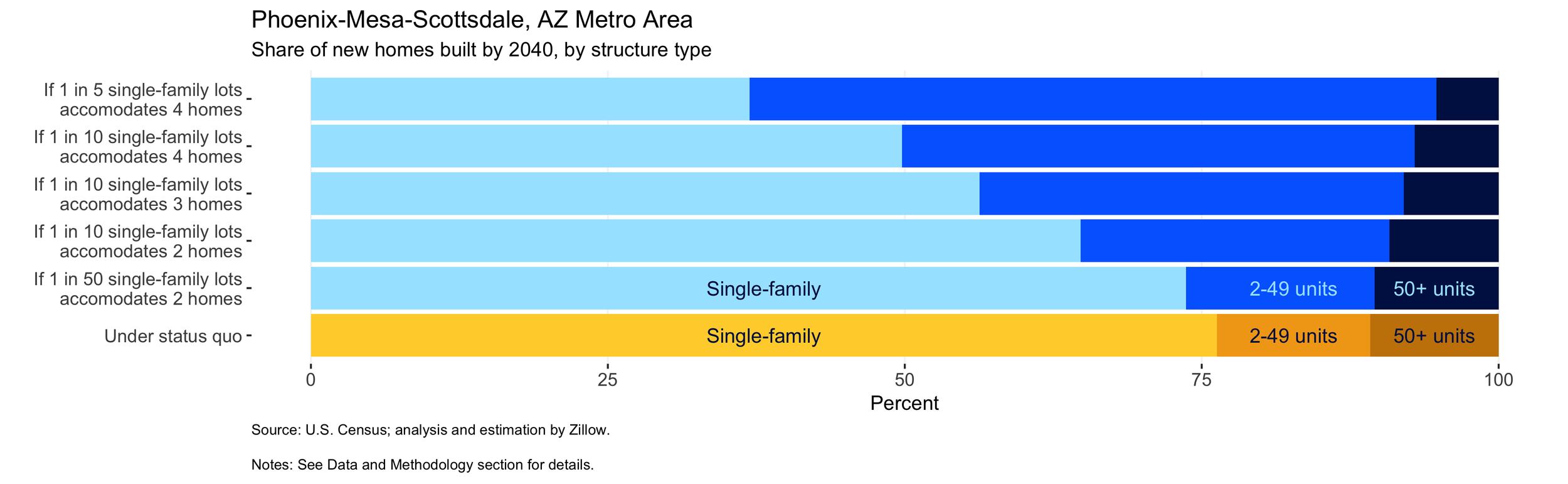

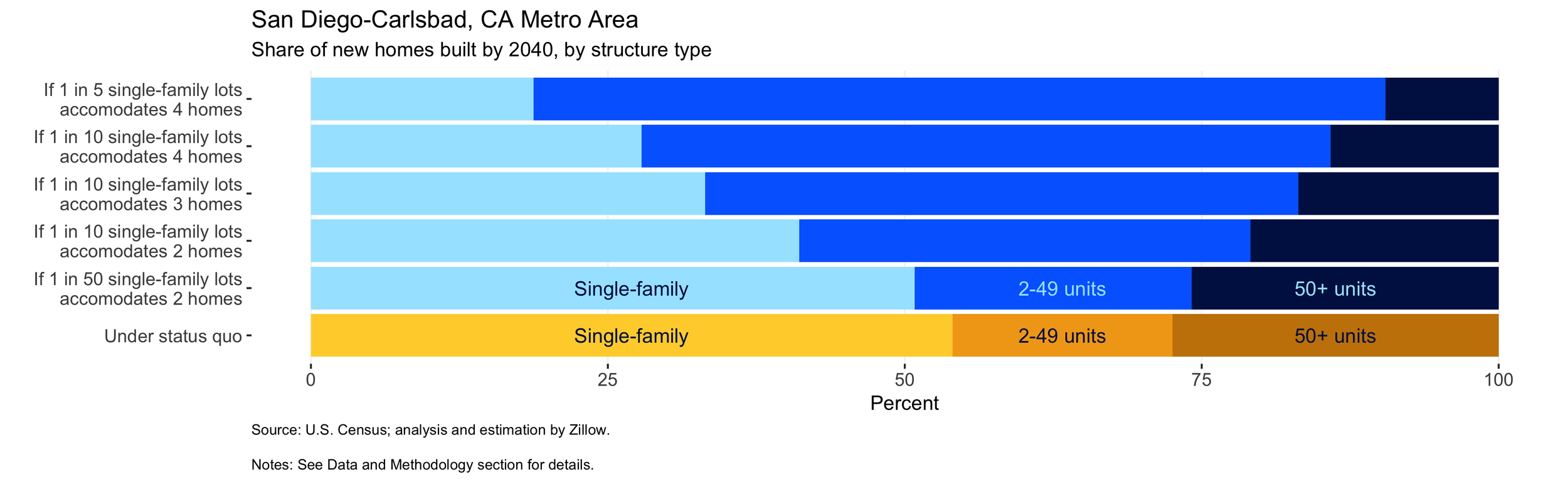

Modest densification could enrich the mix of housing types being built

Click on the chart to move to the next metro area:

Reality Check

While this kind of back-of-the-envelope math can sound enticing, there are any number of practical limitations and reasonable objections to broad-based densification. Increasing the number of residents that can live on a given block is likely to increase traffic congestion and/or make parking more scarce – especially in suburbs where transit networks are thinner and residents are more reliant on cars. There are also concerns that densification, however gentle, risks altering the very thing that makes less-dense locales desirable – namely their privacy, quiet and space to grow.

But not densifying these areas would simply divert new potential residents elsewhere – typically farther from the urban core (or from the region altogether) – and with them their contribution to congestion and emissions. Densification could also help residents live closer to employment and help alleviate congestion by reducing the amount of travel per resident. And modest densification could help improve public transportation, which tends to get better with density.

Ultimately, despite the precedents set in Minneapolis and Oregon, densifying single-family areas remains a steep uphill political battle. And even if the legal barriers to modest densification were removed, the capacity of the construction industry to take on modest-density infill projects and the virtual absence of a suitable development finance ecosystem would quickly emerge as significant limitations. Still, it’s clear that even modestly re-working these vast, existing swathes of single-family America could radically alter the math of new home production.

And in the midst of the current housing affordability crisis, that ought to have great appeal.

Notes

[1] According to the Zillow Home Value Index, Sept. 1999-Sept. 2019, adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index for all urban consumers, all items in U.S. City Average (CPIAUCSL).

Data & Methodology

Information on the existing housing stock draws from the 2013-2017 5-year compilation of the American Community Survey. The status quo estimates of 2020-2040 housing production by structure size category draw on the same ACS data, and were obtained using a vector autoregression model. Observations in the model correspond to metro x time interval cells for the 18 U.S. metro areas included in this analysis with 2010 population over 3 million residents, and for the five 20-year intervals spanning the period 1940 to 2040.

The model is specified as Yct = A1Yc,t-1 + A2Yc,t-2 + Bh(c)Tt + qc + ect, where:

Yct is 3×1 vector of the log number of currently existing housing units in metro c whose construction vintage is in 20-year period t, with the first element corresponding to single-family homes, the second element to homes in 2-49 unit structures, and the third element to homes in 50+ unit structures.

A1 and A2 are 3×3 coefficient matrices.

The element Bh(c)Tt amounts to a trio of linear time trends specified separately for metros in each housing price tercile.

Specifically, the subscript h(c) corresponds to metro c’s housing price tercile as of January 2010 among the 18 U.S. metros with 2010 populations over 3 million (metropolitan housing price levels were obtained as the Census-observed housing unit weighted average of county-level Zillow Home Value Index levels).

Bh(c) is a 3×3 matrix of coefficients specific to each housing price tercile.

Tt is 3×1 vector of identical elements each of which is a linear index of the time periods, with the 1940-1960 period corresponding to 1 and the 2020-2040 period corresponding to 5.

qc is a 3×1 vector whose elements are identical metro-specific fixed effects.

ect is a 3×1 vector of error terms.

The crucial element in the model is the housing price tercile-specific time trend, which allows the model to capture American cities’ overall trend towards the islands of density in a sea of no-growth pattern, and to do so with different intensities for metros depending on their historic housing price appreciation (as reflected in January 2010 levels). Housing production numbers for the 2000 to 2020 period were estimated based on data from the 2013-2017 5-year ACS under the assumption that housing production already observed in the 2000-2020 period will continue at the same average pace through the end of the period.

Finally, although the Miami region remains in the model, its estimates of 2020-2040 housing production did not seem reasonable and the region was therefore omitted from the brief, despite having a population in excess of 3 million.